GMP SOP

Good Medical Practice - USA

| |  |

Guide to Good Medical Practice – USA is a tool that has been developed to describe desirable characteristics of competent physicians licensed to practice medicine in the United States. It has been developed to provide guidance for physicians and those who educate and regulate them. Individuals from approximately 60 organizations have contributed to writing, reviewing, and editing its content.

It is a living document, meaning that it will evolve and change as input and feedback is received and as medical practice changes. It is written for physicians, but will also assist members of the public in understanding what they may expect of physicians.

Comments and feedback from diverse perspectives will be critical to the document’s continued development and utility to those with a vested interest in assuring physicians are competent. Anyone may review and provide feedback on the Guide to Good Medical Practice – USA using the registration and login shown to the right .

• To download the PDF version of GMP-USA,

HeyNosf Inc. Digital Transformation

HeyNosf Inc. is a communication agency that was founded in 2006, by Jean-Louis Dewinter. He always had a strong interest in languages and decided to create a company reflecting his own interests.

Fallanzy Integration Explained

Fallanzy has been active in the workspace design and ergonomics consulting business for over 20 years. Discover how we answered to the challenges of this company.

Hotels Improvement Study

Our solution is suitable for Hotels as well. We help management to optimize their time and employee to be more efficient and more productive. Discover our study.

About Guide to Good Medical Practice – USA

For thousands of years, physicians have understood that medical practice “demands placing the interests of patients above those of the physician, setting and maintaining standards of competence and integrity, and providing expert advice to society on matters of health.”1

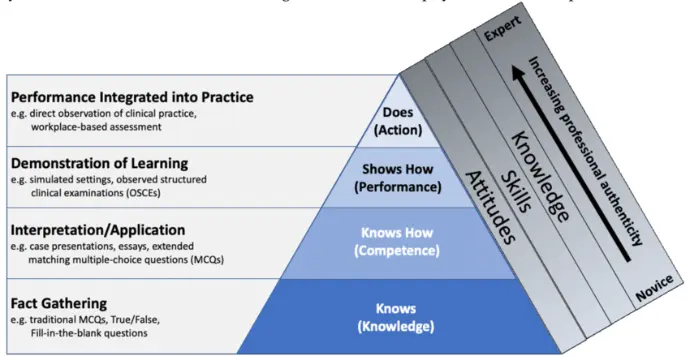

In this document, competence means being qualified in the specific range of skill, knowledge, and ability to perform in a defined role. This document describes desirable characteristics of competent physicians licensed to practice medicine in the United States. Its authors believe that a good physician will strive to achieve these competencies. We also recognize that the setting and context of care influence medical practice, and future uses of these descriptions should reflect the context of care provided by the individual physician. Many factors external to the physician, including the healthcare delivery system and patient behaviors, influence the ability of the physician to demonstrate the characteristics outlined here.

The various entities responsible for educating physicians, accrediting institutions, privileging/credentialing, certifying, and licensing physicians currently have no common language or framework for fulfilling their responsibilities in a consistent, coordinated manner. A Guide to Good Medical Practice – USA is explicitly intended for the first time to provide common language and a common framework for those organizations. It is further hoped that this document will support the development of a common view of professional responsibility among individual physicians.

Physicians should be familiar with the competencies within GMP-USA in their professional roles. As professionals, we base our judgment in applying the principles of this document to the various situations we face, whether or not we routinely see patients. Concepts in this document are not intended to be prescriptive or regulatory in and of themselves; rather, they provide a common frame of reference for the entities with those responsibilities. We recognize that physicians’ performance and clinical outcomes are not synonymous with competencies, but competencies should promote better outcomes and are more likely to do so.

We recognize that further development of the principles and examples included in this document will require additional, ongoing elaborations of these competencies for physicians in specific specialties. We expect that specialty colleges, boards, and other organizations with responsibility for specific areas of medical practice will provide additional guidance for specialists using the principles and framework provided by GMP-USA.

We acknowledge that error is human and that non-punitive admission of error can contribute to quality improvement. The concepts in this document are intended to stimulate educational efforts for continuous quality improvement by providing a common language and taxonomy for discussing the profession’s expectations of physicians. This document is a guide and is not intended to be used as a standard.

The first section of Good Medical Practice – USA contains a summary of the competency categories and their major subcategories. These "Domains of Competency" are followed by an Appendix containing six chapters, each providing examples intended to help define one general competency:

- Patient Care

- Medical Knowledge and Skills

- Practice-based Learning and Improvement

- Interpersonal and Communication Skills

- Professional Behavior

- Systems-based Practice

These competencies are interdependent; many behaviors can be categorized in several competencies. While chapter and sub-chapter headings are provided to help organize the document, the substance is in the specific guidelines.

Domains of Competency

A summary of key principles; examples that help define these principles are provided in Appendix 1.

Good physicians care for patients. We:

- provide care that is compassionate, appropriate, and effective for the diagnosis and treatment of health problems, the promotion of health, and the prevention of disease;

- approach care as a cooperative endeavor, addressing the patient's health needs and concerns;

- make the care of the patient our first concern;

- seek to provide optimal care while adhering to accepted standards of care;

- minimize risk, harm, and opportunities for errors and adverse events;

- collaborate effectively with other members of healthcare teams to provide effective care.

Good physicians maintain knowledge and skills. We:

- demonstrate up-to-date knowledge and the application of that knowledge to patient care and public health;

- maintain technical proficiency in the clinical skills relevant to our practice;

- apply knowledge and skills with an understanding of each patient's needs in order to provide patient-centered care;

- seek and apply guidelines and best practices in making individual patient care decisions;

- ensure that our scope of practice remains within our own competence.

Good physicians actively learn from their practices. We:

- thoughtfully assess our own practices;

- assimilate scientific evidence;

- seek always to improve patient care practices.

Good physicians exhibit excellent interpersonal and communication skills. We:

- actively listen to patients, their families, and colleagues and speak with them clearly and honestly;

- exchange information and collaborate effectively with patients' families, healthcare teams, and professional associates.

Good physicians exhibit commitment to the ethical and professional standards of the medical profession. We:

- are honest and trustworthy and honor the trust placed in us;

- care for our own health to ensure patient safety;

- are responsive to the needs and wishes of patients and society and subordinate our self-interest in fulfilling our professional responsibilities;

- remain accountable to patients by

- demonstrating sensitivity to patients' individual characteristics and providing appropriate care regardless of patient characteristics or beliefs,

- treating information about patients as confidential,

- obtaining consent from patients for investigations and interventions,

- being accessible or ensuring that competent alternate care providers are available to the patient,

- being honest and transparent in business practices, and

- avoiding and disclosing any conflicts of interest that might affect the care we provide;

- treat colleagues fairly and with respect and hold them accountable for the standards of the profession;

- are committed to excellence and ongoing professional development;

- recognize our responsibilities to society.

Good physicians practice effectively in systems of healthcare. We:

- are aware of the healthcare system in which we work and adapt the care we provide to its realities, while making the best interests of our patients our first priority at all times;

- make effective use of system resources to provide optimal care;

- recognize how our actions affect the larger healthcare system;

- participate in efforts to improve safety and quality of care for patients;

- recognize the value of teaching and training others.

APPENDIX 1

EXAMPLES OF APPLYING THE COMPETENCIES

The content of the following chapters provides examples of behaviors that exemplify each general competency. They are provided to encourage a common understanding of the meaning of the general competencies and guidance in adapting the general competencies for educational or evaluative purposes. Redundancy is present where a behavior may apply to more than one competency. The examples are not exhaustive. They include behaviors ranging from those that would be expected of any physician at any time to those that require judgment to determine if they are applicable in a particular situation because of factors outside the control of the physician, such as healthcare delivery system characteristics and patient behaviors.

Chapter 1:

PATIENT CARE

Physicians provide patient care that is compassionate, appropriate, and effective for the diagnosis and treatment of health problems, the promotion of health, and the prevention of disease.

Good patient care is always a cooperative endeavor with our patients; it addresses the patient's health needs and concerns.

In providing care, we:

- make the patient our first concern;

- seek to provide optimal care while adhering to accepted standards of care;

- minimize risk, harm, and opportunities for errors and adverse events.

1.1 Compassionate care

We communicate effectively and demonstrate caring behaviors when interacting with patients and those within their support system.

We:

- respect each patient's dignity and individuality;

- treat every patient considerately and respect the patient's time; listen carefully and considerately to patients and their relatives;

- create, convey, and maintain a sense of caring, trust, and humanity;

- counsel and educate patients and their families;

- are sensitive and responsive in providing information and support for relatives, guardians, caregivers, partners, and others close to the patient while respecting the patient's autonomy and prior requests, including after a patient has died.

1.2 Gathering information from patients

In our practice of medicine, we gather essential and accurate information about our patients.

We:

- adequately assess the patient's condition(s);

- take an adequate history (including the symptoms, psychological and social factors); understand the patient's living circumstances and support structure,

- understand the patient's views;

- examine the patient as thoroughly as necessary, while providing for the patient's comfort and privacy.

1.3 Maintaining health

We are expected to provide healthcare services aimed at preventing health problems and at maintaining health.

We:

- encourage patients to understand and take action to improve and maintain their health; support patients in the self-care of chronic conditions;

- advise patients on the effects of their life choices on their health and well-being and the outcomes of their treatments;

- direct patients to resources that will support them in making the changes necessary to enhance their health;

- offer patients appropriate preventive measures, such as screening tests and immunizations, that are appropriate to their particular health status and consistent with guidelines and best practices;

- support the promotion of health in the community beyond our patients.

1.4 Managing patients' health

We make informed decisions about diagnostic and therapeutic interventions based on patient information and preferences, up-to-date scientific evidence, and clinical judgment.

1.4.1 Diagnosis and treatment

We:

- give priority to the care of patients on the basis of clinical need, when such decisions are within our power;

- identify the patient's most significant problems and diagnoses based on all available evidence and reach agreement with the patient on the priority of identified problems;

- provide or arrange for advice, investigations, or treatment based on available evidence and in accordance with our patients' preferences and living circumstances, including those related to cost and cultural expectations, and our clinical judgment about likely effectiveness;

- prescribe treatment only when we have adequate knowledge of the patient's health, lifestyle, and capacity for cooperation and are satisfied that the treatment serves the patient's needs;

- perform competently all invasive and non-invasive procedures essential for the area of our practice;

- apply guidelines focused on patient safety, including simple habits like hand-washing.

1.4.2 Putting the patient's interest first

We:

- respect patients' rights to engage with us in a manner that respects their autonomy and empowers them to take charge of their own healthcare and make decisions in their own best interests to the extent they choose;

- facilitate patient access to appropriate materials and information technology to support care decisions and education;

- promptly explain the results of investigations to patients;

- treat patients with respect whatever their life choices and beliefs;

- treat patients even though their actions may have contributed to their condition;

- ensure that our personal views do not affect the quality of our professional relationship with patients or the treatment we provide or arrange;

- adapt our care to the effects of our patients' age, ethnicity, gender, and health beliefs as indicated by evidence;

- avoid differences in treatment of similar patients if the differences are not based on evidence,

- assist patients in selecting hospitals or other institutions when needed for their care;

- help patients understand any limits imposed on their care by their insurance providers.

1.4.3 Managing special circumstances

We:

- make efforts to anticipate the patient's pain' and distress and take steps to alleviate or manage them;

- provide effective and compassionate end-of-life care;

- offer assistance in an emergency, wherever it may arise, taking account of safety, our competence, and the availability of other options for care;

- treat patients even though their medical condition may put us at risk; when a patient poses a risk to our health or safety, however, we should take whatever steps are necessary to minimize the risk or make suitable alternative arrangements for treatment.

1.4.4 Ending our relationship with a patient

Circumstances arise occasionally in which we may find it necessary to end our professional relationship with a patient. We should not end a relationship with a patient solely because of a complaint the patient has made about us or our team. When we do end a professional relationship with a patient, we:

- are certain that our decision is fair,

- are prepared to justify our decision;

- inform the patient of our decision and the reasons for ending the professional relationship, and do so in writing whenever practical;

- assist the patient in finding an alternate appropriate source of care.

1.5 Collaborating to provide care

Good patient care requires that we cooperate with colleagues and work with healthcare professionals, including those from other disciplines. Sharing information with other healthcare professionals is essential for safe and effective patient care.

1.5.1 Entrusting patients to colleagues

We:

- consult and take advice from colleagues, when appropriate, and negotiate when conflicts exist;

- refer a patient to another qualified practitioner, when in the patient's best interests; respect the patient's right to seek another opinion;

- ensure that arrangements are made for the continuing care of the patient by an appropriately qualified professional when we will not provide that care;

- ensure that, when we are off duty, suitable arrangements have been made for our patients' medical care, including effective hand-off procedures in which responsibilities are clearly delineated and communicated;

- ensure that, when the responsibility for the patient is being transferred to another provider or another care setting, expectations and responsibilities have been clearly delineated and communicated;

- perform agreed upon roles and responsibilities as a member of healthcare teams.

1.5.2 Communicating to colleagues about patients

We:

- keep clear, accurate, timely and legible records, reporting the relevant clinical findings, the decisions made, the information given to patients, and any drugs prescribed or other investigation or treatment;

- communicate appropriate and timely information about the patient and the patient's condition to other members of the healthcare team;

- communicate the expectation that other team members provide appropriate information back to us.

Chapter 2:

MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE AND CLINICAL SKILLS

We demonstrate up-to-date knowledge about basic medical, clinical, and related sciences, and the application of that knowledge to patient care and public health. We maintain technical proficiency in the clinical skills relevant to our practice. We apply our knowledge and skills with an understanding of each patient's needs in order to provide patient-centered care.

2.1 Maintaining up-to-date knowledge and skills

We apply the basic and clinically supportive sciences and skills that are appropriate to our scope of practice in the context of the best available medical evidence.

We:

- take personal responsibility for maintaining up-to-date knowledge of basic science and clinical medicine and up-to-date clinical skills in areas relevant to our practice;

- promptly modify our practice to incorporate evidence-based improvements in care;

- engage in a systematic program of self-assessment of our medical knowledge and skills; develop individual learning plans that focus on areas of weakness;

- engage in periodic reassessment to evaluate improvement and to direct continued learning, participate regularly in learning activities that are relevant to our practice;

- complete appropriate training before undertaking new procedures or practices.

2.2 Accessing and evaluating information

We demonstrate scientific rigor in dealing with clinical situations.

We:

- seek timely answers to questions that arise at the time of care using appropriate information sources and databases;

- engage in a review of the medical literature and other sources of medical information, evaluate the quality of evidence, assess its relevance to our specific needs, and integrate the information into our daily practice;

- maintain critical thinking skills and use decision-support tools appropriately;

- understand and are able to explain the limitations of medical knowledge, using our clinical judgment to provide care for patients when knowledge is insufficient.

2.3 Understanding our own limits

We ensure that our scope of practice remains within our own competence.

We:

- are aware of the boundaries of our knowledge and skills;

- participate in ongoing, practice-specific assessment of our knowledge and skills;

- undertake only those procedures or practices that fall within our scope of competence;

- always state our qualifications, skills, or experience truthfully;

- refer a patient or seek help from qualified colleagues when the patient's problem cannot be managed within the boundaries of our own competence.

2.4 Adhering to guidelines and best practices

We adhere to established guidelines and best practices.

We:

- regularly review established evidence-based practice guidelines germane to the scope of our practice;

- adhere to these guidelines or document a rationale for deviating from them;

- use our best clinical judgment when guidelines are not appropriate for our patient's specific circumstances;

- adhere to the codes, laws, and regulations of practice relevant to our work;

- consider the information that patients bring about their conditions using evidence-based standards.

Chapter 3:

PRACTICE-BASED LEARNING AND IMPROVEMENT

We thoughtfully assess our own patient care practices, assimilate scientific evidence, and seek always to improve our patient care practices.

3.1 Evaluation of patient care practices

We regularly:

- assess ourselves and seek useful assessment by others;

- collect and analyze information from our medical practice, documenting our own evaluation of the care we provide in the context of evidence-based guidelines wherever possible; analyze practice experience, including feedback from patients, their care experiences, and their outcomes.

3.2 Appraisal of evidence and enhancement of knowledge

We:

- use information about our own patients and the larger population from which our patients are drawn to guide our learning.

- assimilate evidence from scientific studies related to our patients' health problems;

- apply knowledge of study designs and statistical methods to the appraisal of clinical studies and other information on diagnostic and therapeutic effectiveness;

- take part regularly in learning activities that maintain and advance our competence and performance.

3.3 Improvement of patient care practices

We:

- apply the outcome of audits, appraisals, and performance reviews to our practice;

- undertake further training and professional development when appropriate;

- implement changes in our performance and improvements in practice that incorporate feedback from patients and colleagues;

- apply best practices and available benchmarks to our own patient care;

- work with colleagues and patients to maintain and improve the quality of our work and promote patient safety,

- measure the effects of changes we make in our practice to support further improvement.

In order to learn and improve, we take whatever advantage we can of information technology to:

- manage information about our patients;

- access medical information relevant to our practice;

- support our own education.

Why Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) are Crucial for Biotech and Pharmaceutical Industries ?

Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) are essential to ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of products in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical sectors. By adhering to GMP guidelines, companies ensure that their products meet strict regulatory standards, providing confidence to both healthcare providers and patients.

In this post, we’ll explore why GMP compliance is critical for the biotech industry, the benefits it offers, and how your company can maintain the highest standards of product quality and manufacturing integrity.

What are Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) ?

Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) refer to a set of regulations and standards enforced by regulatory agencies such as the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) and EMA (European Medicines Agency). These practices ensure that products are consistently produced and controlled according to quality standards. GMP is particularly important in the production of pharmaceutical drugs, biologics, and medical devices.

Why GMP Matters for Biotechnology and Pharmaceuticals ?

- Ensures Product Quality and Safety : The primary purpose of GMP compliance is to guarantee the safety and efficacy of drugs and biologics. From raw material sourcing to final product testing, GMP ensures that every step of the production process meets rigorous standards.

- Reduces Risks of Contamination : Contamination is one of the most significant risks in pharmaceutical and biotech manufacturing. By adhering to GMP guidelines, manufacturers can minimize the risks of contamination during production, storage, and transportation, ensuring a safe end product.

- Facilitates Regulatory Compliance : Compliance with GMP is required by regulatory agencies to ensure the marketability of pharmaceutical and biotechnology products. Companies that fail to comply with GMP guidelines risk facing delays in product approval, costly fines, or product recalls.

- Improves Consistency and Reliability : By maintaining a strict adherence to GMP, manufacturers can ensure that their products are consistently produced to the same high standards. This consistency is vital in building brand trust and ensuring patient safety.

- Enhances Efficiency and Reduces Costs : While implementing GMP requires initial investment, it ultimately leads to improved manufacturing efficiency and reduced errors, rework, and waste. This not only saves costs but also contributes to streamlining the production process.

Key Elements of GMP Compliance

- Quality Management System (QMS) : A robust QMS ensures that manufacturing processes are defined, documented, and continuously evaluated.

- Documentation and Record Keeping : Accurate and detailed records of manufacturing processes, materials, and testing are essential for traceability and regulatory inspections.

- Personnel Training : Ensuring that employees are properly trained in GMP guidelines is critical to maintaining product integrity and safety.

- Facility Design and Equipment : The manufacturing environment must be designed to minimize contamination risks, including air handling, equipment calibration, and sanitation.

GMP Compliance for Biotech and Pharmaceutical Companies

For biotech companies involved in the development and production of biological drugs, ensuring GMP compliance is essential. From the production of cell cultures and genetically engineered products to the final packaging of biopharmaceuticals, GMP guidelines ensure that the entire process meets the highest standards for purity, potency, and safety.

In pharmaceutical companies, GMP compliance extends to the production of oral medications, injectables, and topical treatments. Adhering to GMP standards guarantees the quality and efficacy of these medications, preventing the introduction of defective or contaminated products into the market.

How to Ensure GMP Compliance in Your Company

- Establish Strong Internal Processes : Implement a comprehensive Quality Management System (QMS) that integrates GMP principles at every stage of production.

- Regular Audits and Inspections : Conduct regular GMP audits to ensure that all processes are compliant and identify areas for improvement.

- Employee Training : Provide ongoing training to all personnel involved in the manufacturing process to ensure they understand and adhere to GMP standards.

- Documentation and Record Keeping : Maintain detailed records of all manufacturing activities, including raw material sourcing, batch production, testing, and distribution.

Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) are more than just a regulatory requirement—they are a critical component in ensuring the safety, quality, and efficacy of pharmaceutical and biotechnology products. By adhering to GMP, companies not only comply with industry regulations but also improve the quality of their products, reduce risks, and build trust with consumers and healthcare professionals alike.

Whether you're involved in drug development, gene therapy, or medical device manufacturing, implementing GMP can significantly enhance the reliability and success of your operations.